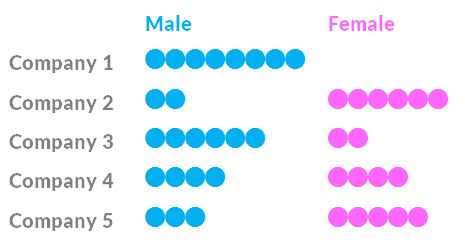

Consider the gender composition of the Board of Directors at 5 companies.

Which company was the least fair when it appointed its 8 board members?

This question echoes familiar claims about the gender balance of leadership teams in companies. Diversity of other forms too.

What does this information tell us about the fairness of each company in making board appointments?

Absolutely nothing.

In fact all 5 companies are fictitious and the board gender composition was generated randomly using coin flips. Every single one of these gender compositions can occur randomly without any causal explanation.

This seems surprising, dissonant. Our brains want to construct plausible stories about possible factors; hiring biases, social responsibility, diversity policies, sector culture etc.

We may still attempt to score, rank, benchmark the diversity of companies using this type of information.

True, the chance of 8 board members of the same sex is far less likely than an even gender split. This is the binomial distribution at work.

This is what statistics is good at: aggregation, summarisation. Statistics can show how gender distribution on boards departs from expected proportions across lots of companies. It can detect true, and unacceptable discrimination at scale. It also helps us to claim with some confidence that groups with shared characteristics are different to others – fashion compared with construction for example – and how that might mirror historic or current social norms.

But we can’t look at the gender of board members at an individual company and make a reliable judgement about whether they were appointed with a gender bias or not. Comparing an individual company to an industry average of some sort isn’t meaningful either. A single-sex 8 person board can occur as a chance outlier rather than by discrimination.

If all our 5 companies truly have a random gender mix, what could they have done differently? Might we actually make a false accusation of bias? Should they have engineered a ‘representative’ gender mix? Or would intervening in a random distribution actually lead to more unfairness?

That’s a dilemma.

One example is how the investment industry compares companies according to their Environmental, Social & Governance (ESG) performance. Some ‘rating’ schemes attempt to score an individual company’s social responsibility based simplistically on the board gender mix. More of one gender = less representative of the population = less socially responsible. Seriously?

At the very least we might try to express the probability of gender bias in an individual company, given base rates (eg. for an occupation, sector) and a binomial expectation. Perhaps thats just not headline-grabbing enough? Do we just want simple claims – such as a gender pay gaps – which confirm our beliefs about unfairness without detecting real, wrongful discrimination?

What does that say about our intuitions when wrestling with the concept of diversity of all forms? Could championing ‘diversity’ as a vague and simplistic ideal even obscure its specific purpose, intent, goals? If we focus on what we can easily see and count, we might fail to seek those true causal factors which make the world a better place.